Image description: A fat blonde woman in a bikini with visible side rolls sits on a vintage red suitcase at the edge of the water on a beach, looking away.

Content note: Dental procedures

I feel like my poor dentist’s office has born the brunt of my ever-spinning analyses this year, while in truth, I love my dentist and her whole office. They were the first dental office to ever treat me with liking or respect.

When I moved cross-country to Washington state in 2014, I’d been so scarred by a lifetime of dentists who neither liked nor respected me that I avoided dental care until the inevitable emergency and picked a dental office with good reviews more or less at random.

When I walked in, they took one look at me and sat me down, got me a drink of water, encouraged me to take an over-the-counter painkiller just in case, and asked if I’d ever considered nitrous before. (I had never even been to an office that offered it.) When I said I was willing to try it, they talked me gently through every step so that I always felt safe and supported, and have ever since. Even when I felt the edge, I have never felt unsafe or disrespected.

My dentist was also the first healthcare provider who recognized my TMJ as anything other than me being strange and difficult, sat me down and had a gentle discussion about it (I, uh, didn’t realize that it’s not normal to not be able to close your mouth for a while after a dental procedure), and referred me to two other providers who were able to treat the underlying issues and help me manage my TMJ.

So, I love my dentist. But this is also the only healthcare provider’s office I’ve been to since the pandemic started, because my serious and necessary dental work could no longer be put off, so they’re bearing the brunt of my pattern recognition and cultural analysis.

The reason I’m telling you this is that when I went in for an appointment last week, the hygienist attending me said something I wasn’t thrilled about regarding her personal level of COVID precautions, or lack thereof. (I won’t tell you what it was, because COVID is not actually the point of this post and I don’t want us to get derailed.)

I happened to mention this on a friend’s Facebook page as one of a number of commenters griping about people doing unsafe things during the pandemic, and was totally taken aback that my comment immediately began accumulating responses…critical of me.

See, the actual problem was me going to the dentist during the pandemic. (Because I definitely volunteer for 7.5-hour dental procedures for fun, on a whim.) No, wait, the actual problem was that I didn’t report the hygienist to the dentist then and there. Or maybe what I should have actually done is call around until I found a dental office taking perfect precautions. Or, or, or. Should, should, should.

And woven through the whole discussion were comments from some people clinging so hard to a just-world fallacy that it made my teeth ache, telling me all about how their dentists are perfect precious jewels of round-the-clock extreme safety.

(Because, of course, if they can believe hard enough that the people around them are perfect, then they won’t get sick, and when someone else gets sick, it’s clearly because they weren’t trying hard enough. That’s a just-world fallacy.)

And it made my teeth literally ache, too. After a couple dozen of these comments, I was so hyperaware of the row of temporary crowns covering the small stubs of my natural-born bad teeth that I fled the discussion in a near panic.

And this is one of the many reasons why marginalized, particularly fat, people tend to avoid medical care unless it’s absolutely necessary. No matter how we choose to navigate a situation, there will be plenty of people ready to tell us that we did it wrong (and imply that negative outcomes are our fault).

But we’re not here to talk about teeth, really.

In a previous Body Liberation Guide, I talked at length about a coworker who’d tried to “save” me from my fatness, including fat-shaming and food-shaming me in an elevator full of people. Some of the responses to that, plus responses to the dentist incident, have me thinking about the ways we use anger and outrage to shield ourselves from self-criticism.

Was what my coworker did fairly terrible? Yes. But it’s too easy to say “well, your coworker was a jerk,” because:

She *wasn’t* a jerk. She was a perfectly pleasant person who was also prone to doing harmful things because she thought she was both meeting a moral obligation and genuinely helping fat people.

And I want to separate these things out because her harmful actions happen pretty much every day to pretty much every fat person. Yes, of course what she did was crappy, but those things are also ubiquitous. Many, many fat people spend their lives *constantly*, on a daily basis, negotiating and trying to cope with and survive being treated like this in almost every interaction they have.

To us, this is normal. That doesn’t make it okay, but it does mean that there are a whole lot of perfectly normal people out there — in fact, most of them — who are also sapping the vitality out of all the fat people they know. (Or for another example, just ask anyone with a chronic illness how they felt the tenth time someone asked if they’d considered trying yoga.)

In the same vein, giving unsolicited advice (and being offended when it isn’t received with the expected amount of gratitude) is so ubiquitous that I’ve had to consistently set boundaries here to prevent being smothered in it (and have lost friends who were offended by having to respect those boundaries).

That doesn’t mean anyone in either group is a bad person, or a jerk, or malicious. Most of these actions aren’t even done intentionally, or with any thought to the effect they might have.

I know that until I started to feel smothered by other people doing it, I had no qualms about dumping unsolicited advice on other people, because I was Helping. In a close parallel, diet culture teaches people that fat folks need to be saved from themselves. That when you fat shame, when you pointedly talk about your diet in front of a fat person, when you stage interventions with your fat family members, you are Helping.

And when someone we like shows that they’ve been hurt by people who are Helping, it’s really easy to — rather than examine the ways our own Helping plays into systems of oppression — immediately distance ourselves. Well, those people over there who Helped certainly are jerks! I can’t believe the nerve of those people!

But those people…are us. I would like to think that I’ve worked through a good deal of my culturally-indoctrinated fatphobia, but I make mistakes all the time on all sorts of levels. Dalia Kinsey was very gentle with me recently when I fumbled around in my white privilege during a recording for her podcast, to name just one way I’ve showed my tail lately. And I would like to think that I’m getting better at sitting with criticism and learning and doing better.

But in the meantime: I’m not saying we’re hypocrites and doing the same things we dislike in others, necessarily, but it’s too easy to say “that person over there is a jerk” in a way that separates us from them, especially when the action that put them in the jerk category is a well-meaning Helpful one.

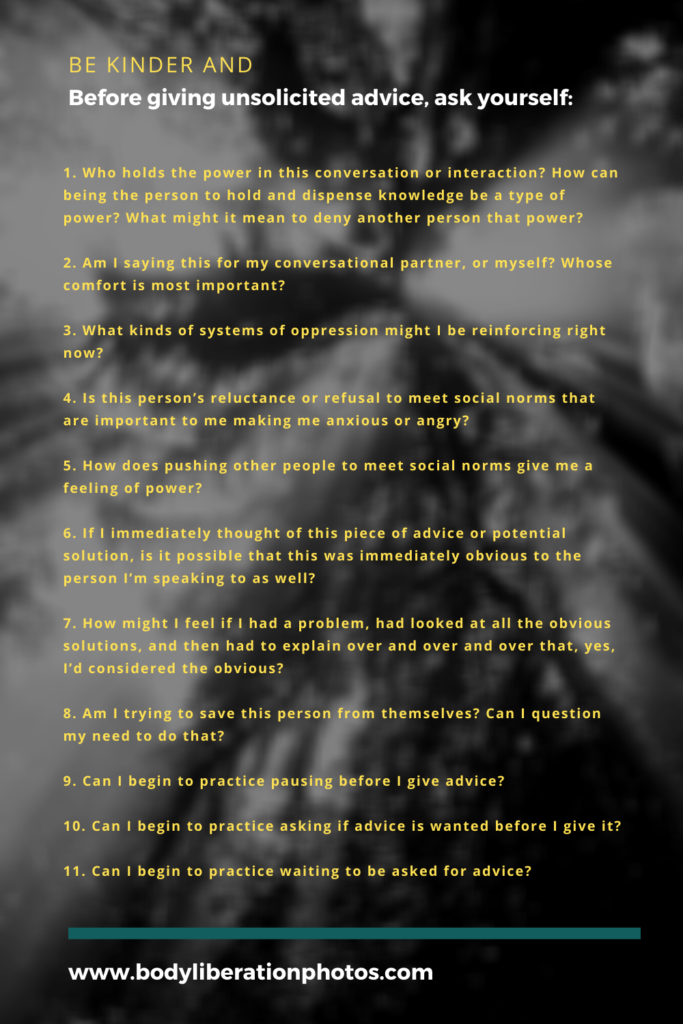

Some questions to ask yourself to begin opening your eyes around Helping:

1. Who holds the power in this conversation or interaction?

2. How can being the person to hold and dispense knowledge be a type of power? What might it mean to deny another person that power?

3. Am I saying what I’m saying for the benefit of my conversational partner, or myself?

4. What kinds of social systems am I reinforcing right now?

5. What kinds of systems of oppression might I be reinforcing right now?

6. Is this person’s reluctance or refusal to meet social norms that are important to me making me anxious or angry?

7. Whose comfort is the most important in this conversation?

8. If the person I am talking to is marginalized, might I be holding some internalized beliefs about the capabilities and intelligence of people in that marginalized group?

9. How does pushing other people to meet social norms give me a feeling of power?

10. If I immediately thought of this piece of advice or potential solution, is it possible that this was immediately obvious to the person I’m speaking to as well?

11. How might I feel if I had a problem, had looked at all the obvious solutions, and then had to explain over and over and over that, yes, I’d considered the obvious?

12. How might I feel if my body were the one seen as such a problem that people were constantly rushing to save me from it?

13. Am I trying to save this person from themselves? Can I interrogate my need to do that?

14. Can I begin to practice pausing before I give advice?

15. Can I begin to practice asking if advice is wanted before I give it?

16. Can I begin to practice waiting to be asked for advice?

Let’s dig deep. Every Monday, I send out my Body Liberation Guide, a thoughtful email jam-packed with resources for changing the way you see your own body and the bodies you see around you. And it’s free. Let’s change the world together.

Hi there! I'm Lindley. I create artwork that celebrates the unique beauty of bodies that fall outside conventional "beauty" standards at Body Liberation Photography. I'm also the creator of Body Liberation Stock and the Body Love Shop, a curated central resource for body-friendly artwork and products. Find all my work here at bodyliberationphotos.com.